The Beginnings: Virtual Existence

The Oriental Institute, founded in 1922, is one of Europe's oldest institutes dedicated to studying the politics, societies, and cultures of "the Orient." The institute is still on paper at this time. The members have not been appointed, and the structure that will serve as the headquarters is still under construction. During this period, the Oriental Institute's first members and President were elected. This gallery showcases key figures, renowned Orientalists, and significant events that shaped the Oriental Institute.

Despite the fact that Oriental research in Czech countries had a long tradition of scholarly output that commanded international respect, the backing for its academic achievements was rather limited. The underprivileged position of the Czech and Slovak nations within the Austro-Hungarian state naturally had an impact on the development of Oriental studies. The Czech University was not re-opened in Bohemia until after 1882. Compared to the Orientalists at the University of Vienna, with their rich tradition of Oriental studies, the Czechoslovak counterparts led a meager existence with the establishment of only one chair. Thus, the first Czech Orientalist in the academic sense, Rudolf Dvořák (1860–1920), professor of Oriental languages, was required to cover a wide range of Oriental fields, from Hebrew and Persian to Chinese. Other fields were studied only as subsidiary disciplines within the context of comparative Indo-European philology, Biblical studies, etc.

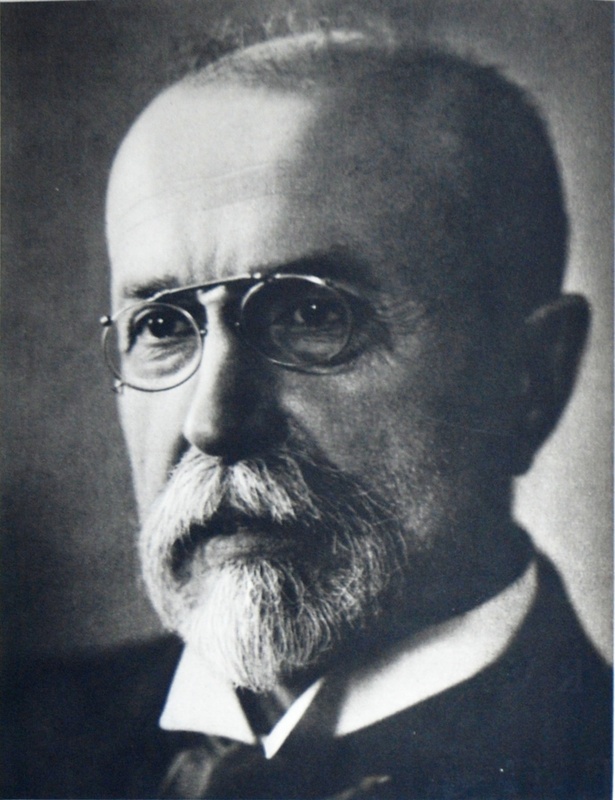

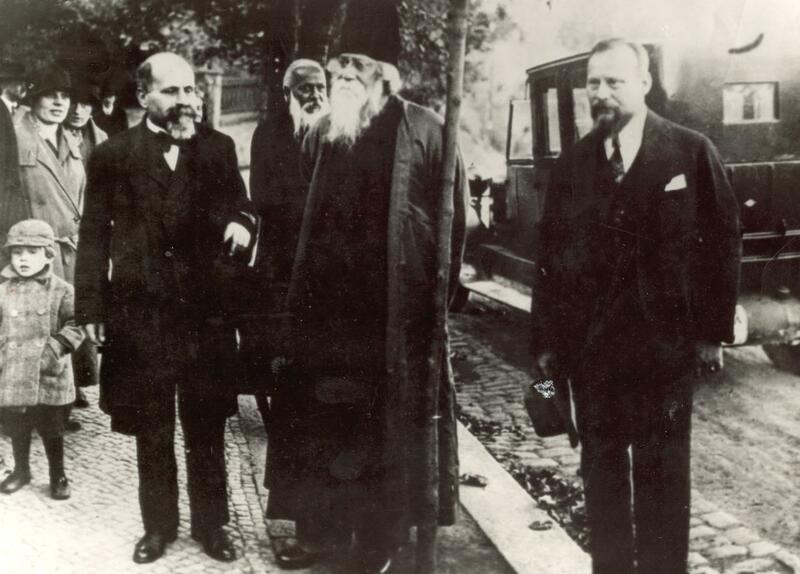

The establishment of the Institute was greatly supported by the first Czechoslovak President, T. G. Masaryk, who provided it with both moral and financial backing. Masaryk was himself a former student of Arabic at the Vienna Oriental Academy. In addition, the war-Odyssey of Masaryk was to take him through Siberia, Manchuria and Korea on his way to Japan, arriving there in 1918. During his short stay in Tokyo and Yokohama his interest was attracted to the cultural and economic activities of the country. His travels through the Far East served to remind him of the manifest importance of the existing cultural and economic relations between Europe and the Orient, and, in all probability, led to the desire to establish an Oriental Institute in his own country. The dream was to be realized when the President’s interest coincided with Professor Musil’s suggestion that a Society for the promotion of cultural and economic relations with the Orient.

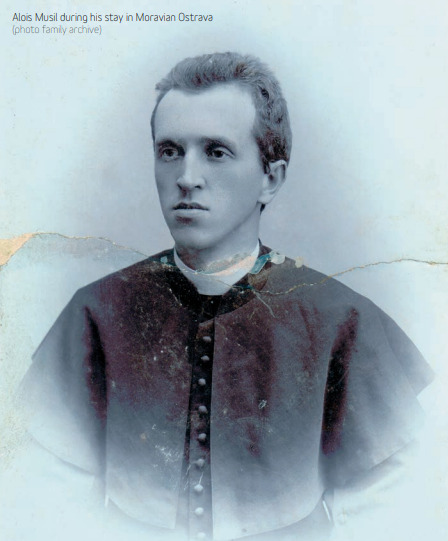

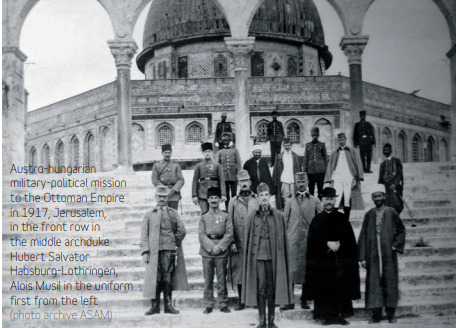

The ever intrepid Alois Musil is one of the first Czech Orientalists engaged in field research, bringing back remarkable findings and materials from his travels in Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula. Among his many interests, geography and ethnology gradually gained sway, as indicated by the first of his monumental works, Arabia Petraea (1907–1908).

Under the auspices of the Viennese Academy, Alfred Hölder published Musil’s four-volume, 1,633-page study, which contained ethnological observations, hundreds of illustrations, an extensive bibliography, and a map supplement. In 1907, he also published his monumental two-volume Kuseir Amra, which deals with his epochal discovery of the Amra palace, built in the Transjordan Desert in the 8th century B.C. Between 1923 and 1928, Musil made several trans-Atlantic trips to New York while preparing his six-volume Oriental Exploration and Studies, published between 1926 and 1928 by the American Geographical Society (AGS), the oldest nationwide geographical organization in the U.S. Besides a detailed description of the explored areas, these books contain many passages dealing with geography, history, and politics In 1927, the AGS awarded Musil its Charles P. Daly Medal for “valuable or distinguished geographical services or labors.” Its first recipient had been the polar explorer Ronald Peary, whose contribution was acknowledged in 1902.

Bedřich Hrozný is known for his decipherment of the Hittite language and contributions to the advancement of Hittite studies. After studying in Berlin and London, and being well versed in Semitic languages, he devoted his attention to Assyriology. In 1914, Hrozný was engaged by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft to publish texts found in the course of the German excavations near the Turkish village of Bogazköy. They were written in a thus-far unknown language, which seemed to have been the official language of the Hittite rulers. In 1917 he published his Die Sprache der Hethiter – a discovery of worldwide importance. In this work, Hrozný deciphered the Hittite script and demonstrated the Indo-European character of the Hittite language. He also greatly contributed to understandings of the whole historical development of the ancient Near East in the 2nd millennium B.C. Hrozný’s discovery became one of the greatest pre-war achievements in Czech science.

From as early as the Middle Ages, Oriental thinking and literature were influential in the Czech and Slovak cultural sphere. The greatest interest of Czech and Slovak scholars in Oriental cultures was initially directed toward the Indian subcontinent. Indian philology as a science began to develop a close relationship with Indo-European comparative linguistics, and its origins are closely linked with the national cultural and political revival in the country.

References and Additional Information