Under the Wings of Academy of Sciences toward Prague Spring

During this period, the Oriental Institute was only recently incorporated into the newly established Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, beginning a new chapter in the Institute's history. The Government Commission for the Development of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences was established by a resolution of the Government of the Czechoslovak Republic on January 15, 1952. The main task of the Government Commission was to build a new scientific establishment, the Academy of Sciences, on the model of the USSR, which was to become the highest scientific institution in the country and was to replace the existing representative scientific societies. The main difference lay in the completely different concept of financing this new institution from the former societies, which received only a limited contribution from the state for their activities.

The members of the Government Commission were also appointed by a government resolution. The selection of members was guided both by their political involvement - and by scientific merit, which means that scientists were selected based on their political orientation and scientific importance. Representatives of mathematical, technical, biological, and social sciences were chosen almost equally. 12 people were members of the Communist Party of the Czech Republic. For the Oriental Institute, it was initially represented by Jan Rypka but for health reasons he relinquished the position to Jaroslav Průšek in March 1952.

The Government Commission at the separate branch congresses introduced the concept of scientists with paid scientific positions, equipped with laboratories and travel and publication opportunities. In less than ten months of its existence, the commission prepared a draft law, built a structure of eight sections that gradually took over and reorganised existing departments, and established new institutes, cabinets and laboratories. Its task was to convince scientists of the coherence and importance of the new institution and the benefits it would bring to scientific activity. The Academy of Sciences has become an important platform, especially for young promising scientists who would otherwise not have had the opportunity to work scientifically due to the lack of positions at universities. At the same time, it became an institution that undermined scientific research and its confusion with state plans and communist ideology.

In the years that followed, the Oriental Institute passed through a period of rapid development. Under the able guidance of Director Průšek, the existing branches of study continued to flourish and many new ones were established (e.g., African studies, Caucasology, Burmese, Siamese, Philippines, Indonesian, Mongolian, Korean, Vietnamese, Tibetan studies, and others). Despite the fact that the ruling regime unduly interfered with scholarly research from time to time, the Institute had attained significant achievements, both at the individual and collective level. The international political context (e.g. the break-up of the world colonial system and emergence of numerous independent states in Asia and Africa) led to the gradual, and welcome, shift of the centre of gravity of research from classical disciplines to the study of modern languages, sociolinguistics, lexicography, modern history, literatures, and more.

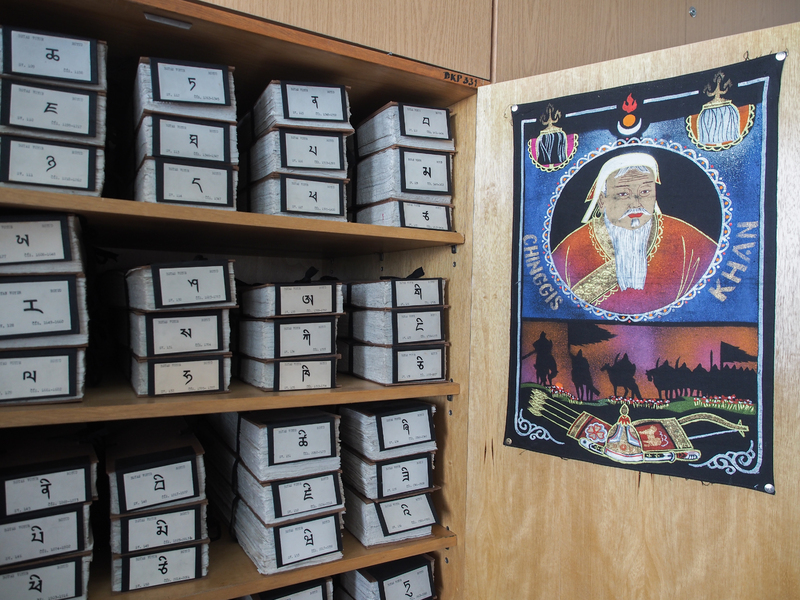

During this period, a notable project is the establishment of Tibetan collection which was set up in 1958. Part of resource is the complete Tibetan Buddhist canon, Kangyur and Tengyur, produced in the East Tibetan town of Derge. The Tibetan Buddhist canon is a loosely defined collection of sacred texts recognized by various schools of Tibetan Buddhism, comprising the Kangyur or Kanjur ('Translation of the Word') and the Tengyur or Tanjur ('Translation of Treatises').

The Korean Library of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic was also founded in 1958. In that year, the Oriental Institute received as a gift several hundred books and periodicals from the Academy of Sciences of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. Most of these books were published in the 1950s, especially after the Korean War. Similar specimens can be found in other post-communist countries in Europe, which also maintained relations only with North Korea at the time. In 1996 and 1997, its collections were considerably enriched by South Korean publications, thanks to generous gifts made by the Korean Foundation.

An important personality in this period is the Sinologist Dana Šťovíčková-Heroldová. On account of the very warm relations between the Czech Republic and the People's Republic of China (PRC), rich cultural, scientific, and scholastic cooperation existed. One of those who were able to study and live in China was the Czech Sinologist, linguist and translator Danuška Šťovíčková-Heroldová . She worked as the first lecturer of Czech at Peking University and at the Institute of Foreign Languages in Beijing between 1953-1957. When she returned to Prague, she gradually managed to convince the director of the Oriental Institute (Prof. Jaroslav Průšek) to compile a high-quality Czech-Chinese dictionary of medium range. Průšek supported the idea and gave the green light to the project. Danuška Šťovíčková was the spirit agent of the entire project and worked on it until her unfortunate departure in 1976.

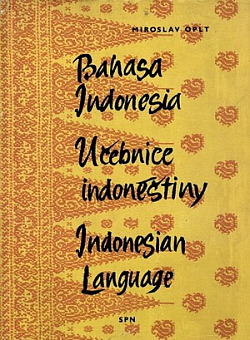

Miroslav Oplt was one of the first teachers of Malay and Indonesian in Czechoslovakia, and wrote the first Czech textbook for learning Indonesian. Czech- Indonesian relations seem to have started as early as the 1950s. In 1956, Miroslav Oplt first traveled to Indonesia on the invitation of then President Sukarno, for whom he had acted as interpreter during the president’s visit to Prague.

Ivan Hrbek was a Czech orientalist, historian, and translator from Arabic. He studied Arabic and Islamic issues from a young age and graduated from the Faculty of Arts at Charles University. He became a prominent authority and world-renowned scientist, working at the Oriental Institute from 1953 until the end of his life. Hrbek was also involved in African history, leading the publication of the two-volume History of Africa and contributing to the Fontes Africae Historiae project and the Histoire générale de l'Afrique. He also wrote chapters for the Cambridge History of Africa and contributed to the Encyclopaedia of Islam. Hrbek published geo-political overviews of Morocco, SAR, and Libya and paid attention to the Palestinian question and the role of Islam in politics in the seventies. He translated key works of Arab philosophers, travelers, historians, and modern authors into Czech. Among his famous works is the Czech translation of the Koran. He also wrote about Arab travelers in Central Europe and Dante Alighieri's relationship to Islam.

References adn Addtional Information

*Adéla Jůnová Macková and Libor Jůn (Eds). 2022. Československo v Orientu: Orient v Československu 1918-1938 = Czechoslovakia in the Orient, the Orient in Czechoslovakia 1918-1938 (Prague: Masaryk Institute and Archive of the Czech Republic, vvi)

Franc, Martin, and Antonín Kostlán [Eds]. "BOHEMIA DOCTA: The historical roots of science and scholarship in the Czech lands." (2018).

Svobodný, P., 2021. Martin Franc–Věra Dvořáčková a kol., Dějiny Československé akademie věd I (1952–1962). AUC Historia Universitatis Carlinae Pragensis, 60(2), pp.112-114.